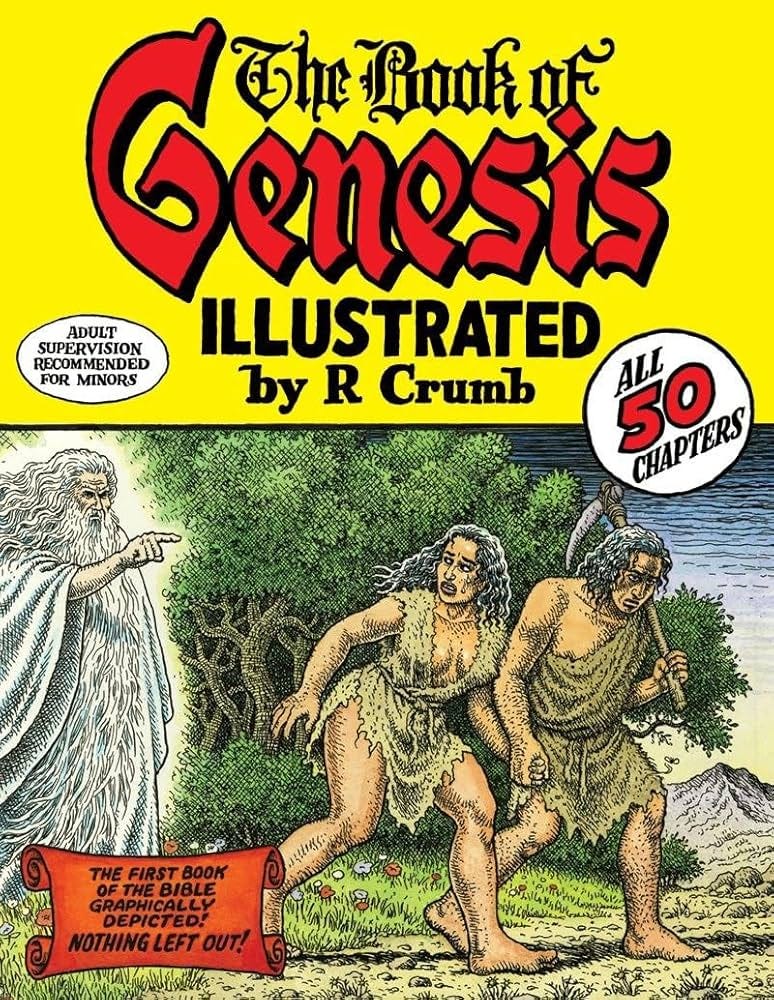

When I was eight years old, I stumbled upon a strange book in my grandfather’s library: The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb.

At first glance, it looked like the comic books I had stacked on my nightstand. But inside, there were no superheroes. Instead, naked, grotesque, all-too-human figures stared up with sunken eyes, rendered in obsessive crosshatching detail. I was repulsed. And enchanted. It was my first encounter with Robert Crumb.

Today is his 82nd birthday, and for nearly six decades Crumb’s work has inspired the same uneasy mix of laughter and disgust worldwide. To some, he’s a visionary. To others, a pervert. But whichever way the cookie crumb-les, one thing is clear: his raw, transgressive comics helped to expand the outer limits of free expression and forced the court and the culture to reckon with what we’d rather keep buried.

It’s perhaps hard to imagine now, but in the 1960s, comics were essentially anesthetized. Under the Comics Code Authority, formed in 1954, publishers were effectively banned from showing sex, drugs, and excessive violence — or anything that might “corrupt young readers” — since distributors generally rejected comics without the Authority’s seal. Superman couldn’t so much as flirt with Lois Lane without a marriage license!

Then along came Crumb.

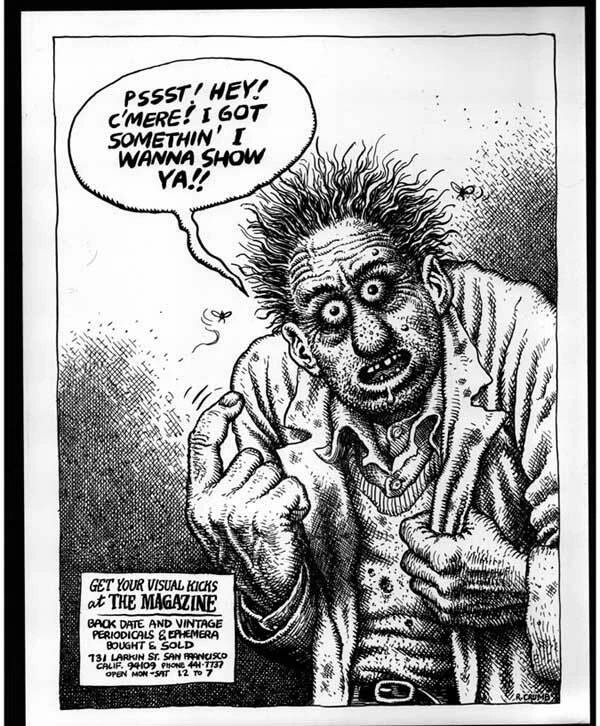

In 1968, he self-published Zap Comix #1, selling copies out of a baby stroller on the streets of San Francisco to the young pilgrims who had just arrived the previous summer in search of free love — and LSD.

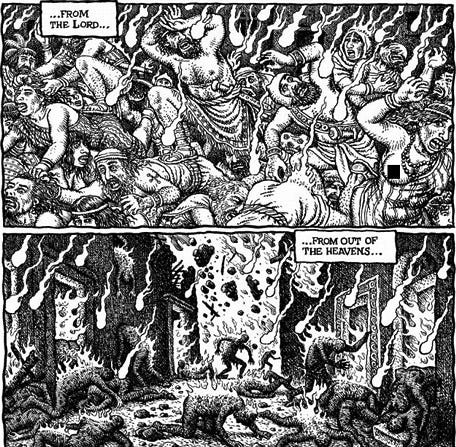

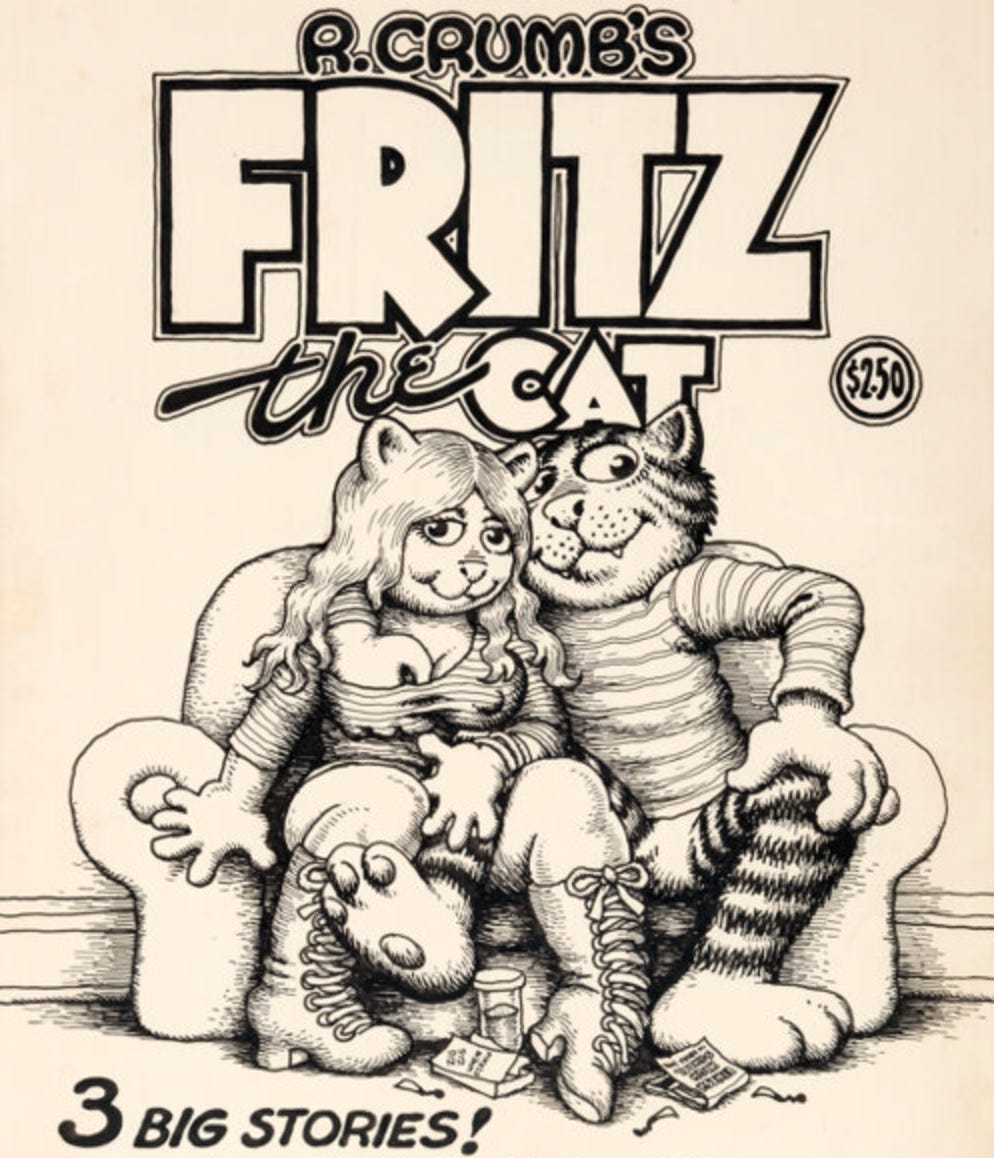

Labeled “For Adult Intellectuals Only,” Zap was like nothing the medium had ever seen. Crumb’s outrageous cast of characters included Fritz the Cat, a lecherous feline drifting between one-night stands and campus protests; Mr. Natural, a bald, bearded guru dispensing half-baked enlightenment; Angelfood McSpade, an oversexed black woman drawn in a Sambo, minstrel-style; and the iconic “Keep on Truckin’” men, endlessly moving forward in their rubber-limbed march.

Zap helped forge the “underground comix” scene, a raucous network of artists and publishers who could finally escape the straitjacket of the Comics Code. In those cheaply stapled pages, anything was possible: sex, blasphemy, sadism, political heresy. But what happens underground, eventually surfaces.

In 1969, the Berkeley police raided a gallery exhibition that dared to hang on their wall Crumb’s “Joe Blow:” a strip featuring a smiling Norman Rockwell-esque, suburban family who spiral into incest. To Crumb, it was an exposure of the rot beneath the idealized image of American domestic life. To the police, it was a threat to public morality. They seized the artwork as contraband, treating ink on paper like narcotics.

The following year, “Joe Blow” stood trial in the 1970 case People v. Kirkpatrick, earning the dubious distinction of being the first comic book to secure an obscenity conviction in the United States. The judge condemned Crumb’s work as “filth for filth’s sake,” saying it had “no redeeming value.”

But Crumb never set out for redemption — only revelation. He held up a funhouse mirror to America, warping its preferred image of itself — prosperous, clean-cut, virtuous — until the distortions revealed the hidden appetites and darkness beneath. Crumb wanted to expose, as he put it, “America the cruel bully; America the glutton; America the greed; America the ugly!”

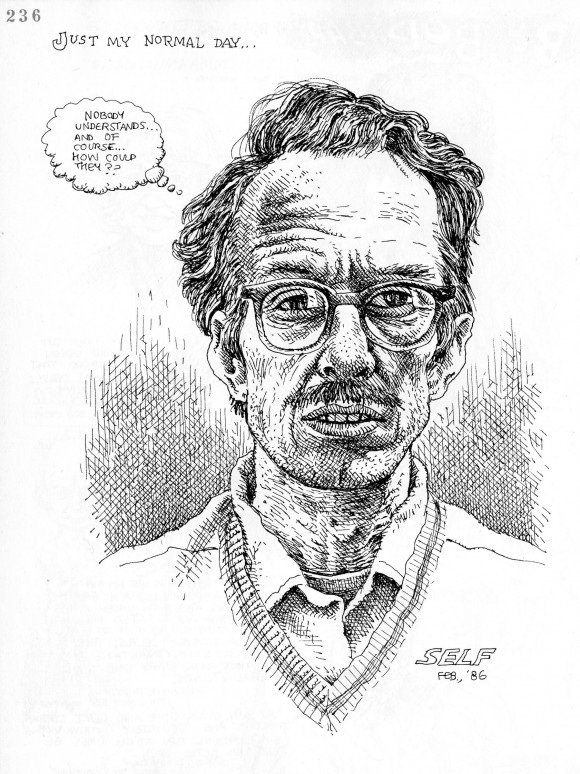

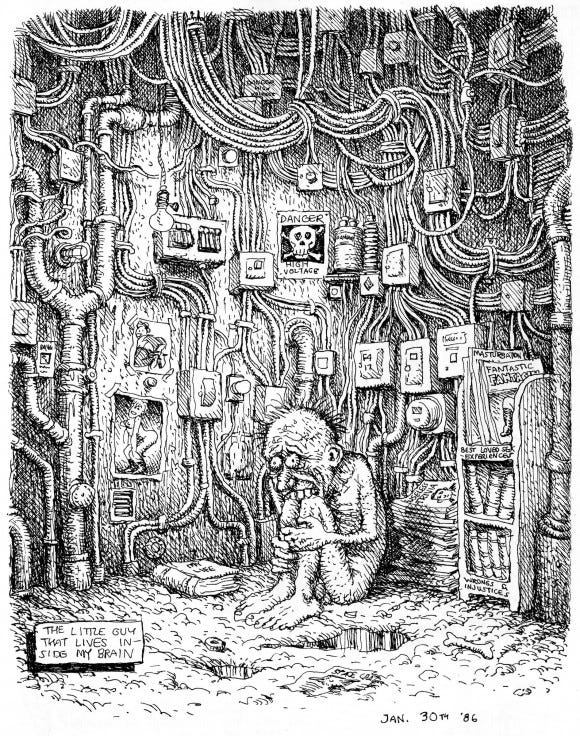

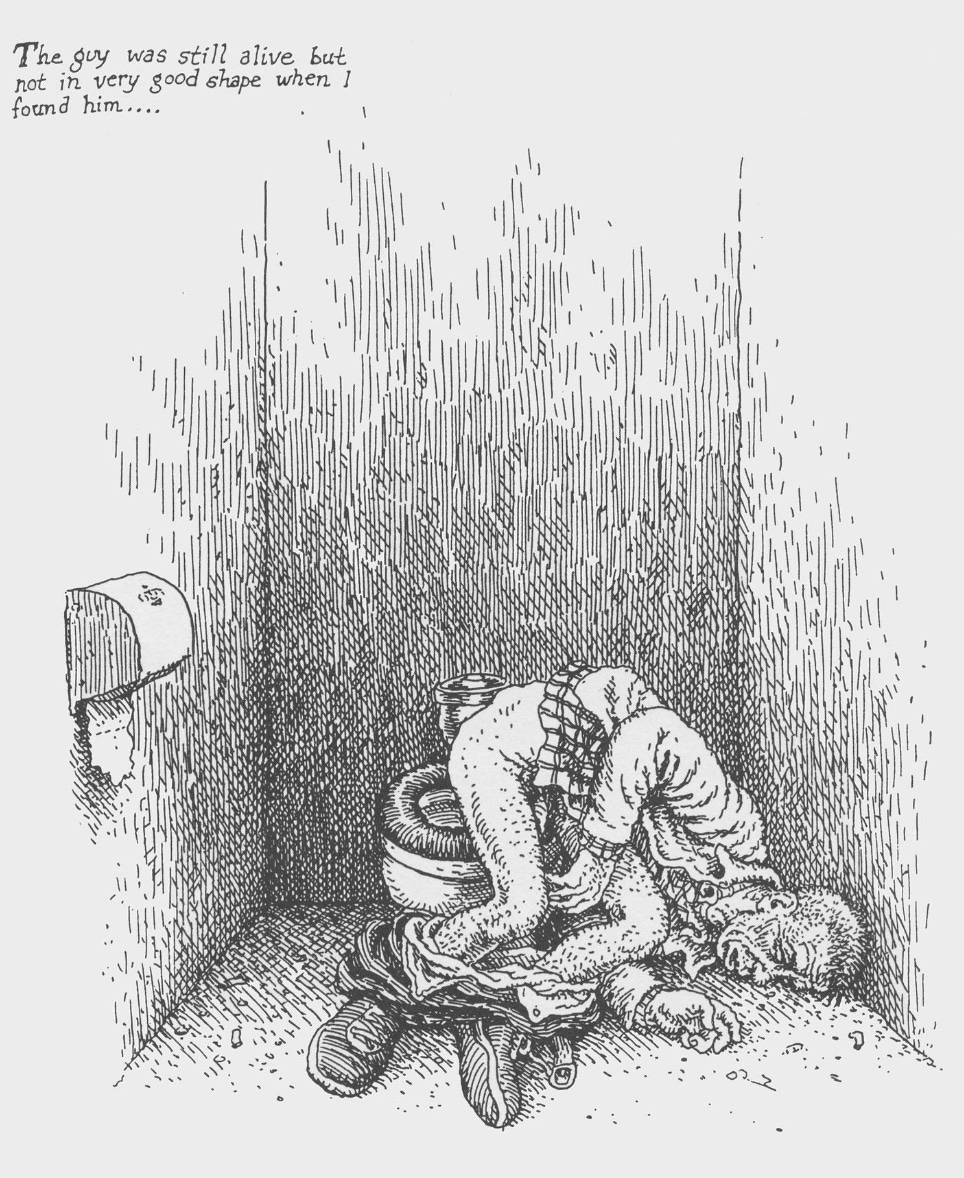

Nor did he exempt himself from this strange little project. In page after page, Crumb turned his pen inward, revealing personal fantasies and fetishes most people work their whole lives to conceal. His sketchbooks became compendia of compulsion: towering Amazonian women crushing him underfoot, violent sexual reveries, pitiful self-caricatures gnawed by loathing and shame.

Readers recoiled. But in recoiling, they often recognized something of themselves. Stray urges, guilty thoughts, embarrassing hungers. Crumb’s art democratized the taboo, insisting such impulses are no less part of our common human inheritance than any other.

This radical self-exposure pushed the boundaries of artistic expression beyond the noble and the sacred, into the disturbing, irrational, and humiliating. It opened the door for generations of artists like Art Spiegelman (Maus) and Alison Bechdel (Fun Home), who proved that comics could grapple with trauma, memory, and identity at the highest level of literary art.

Today, at 82, Crumb watches his native country from a small French village — where he’s been self-exiled for years — content to know that American opinion has generally shifted in his favor since.

Crumb’s work is a reminder that free speech must account for the offensive, for the beautiful is often lurking just underneath.

I return often to that strange book I first discovered in my grandfather’s library. I’m still repulsed and enchanted. But now I’m also comforted: it’s in this mingling of the sublime and the profane, Crumb insists, that the truth awaits. And that the freedom to seek it remains secure, in large part to Crumb — so long as we keep on truckin.’

I loved Crumb's work too for it's ability to reveal what's behind conventional facades. This is vitally important, as long as it doesn't degenerate into national self-hatred with a concomitant desire to self destruct. Throwing the baby out with the bathwater will not provide the means needed for self-correction in pursuit of upholding hard won liberal values.

I was unfamiliar with Crumb before this read. This was a thoughtful and fun introduction to his work!