The Deported

Emma Goldman and activist persecution under the 1917 Espionage Act

In 1919 and 1920, acting under orders from President Woodrow Wilson, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer arrested as many as 10,000 so-called radicals, many of them labor activists, without regard for their constitutional rights. He also succeeded in deporting more than 550 noncitizens. He did this under the authority granted by the Espionage Act of 1917, which made it illegal to obtain information about national defense with reason to believe it could injure the U.S. or aid a foreign nation, and created criminal penalties for obstructing the draft or encouraging military disloyalty.

These arrests became known as the Palmer Raids.

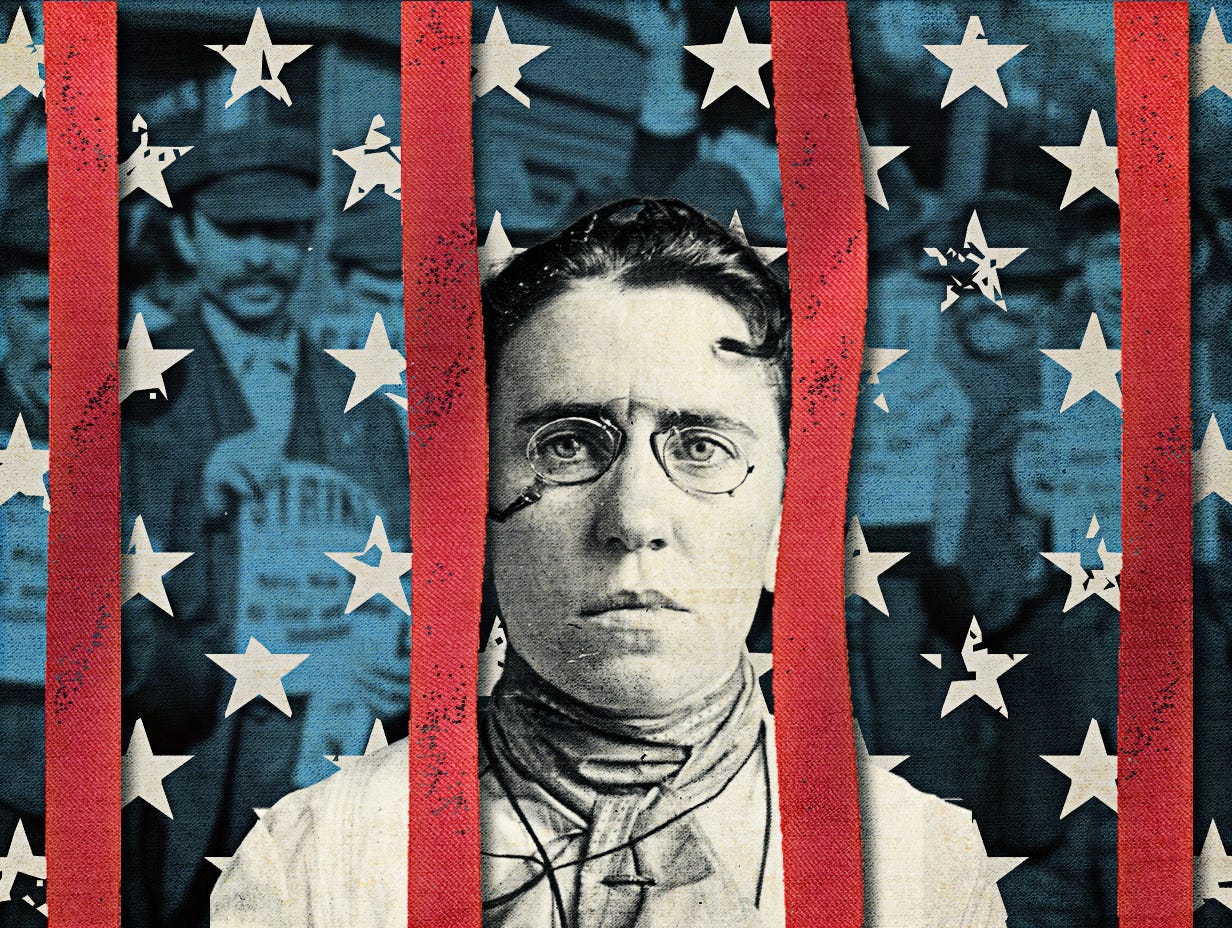

Palmer’s partner was the head of the General Intelligence Division of the Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, who was a mere 24 when he was appointed. Together they oversaw an expansive dragnet to arrest and deport leftist immigrants.

In the dead of night on Dec. 21, 1919, federal agents deported 249 immigrant anarchists, pacifists, and labor activists to Russia, most of them Eastern European Jews, on a leaky Spanish-American warship called the Buford, nicknamed the “Red Ark.” The two most well-known deportees were anarchist and “Mother Earth” publisher Emma Goldman and her friend, former lover, and fellow anarchist Alexander “Sasha” Berkman — both Russian-born, and neither one an American citizen. Goldman had been previously imprisoned for two years on charges of conspiring against the draft. Now, with all appeals exhausted, she was forced to leave the country.

There are echoes of Goldman’s case today, as the Trump administration is attempting to deport noncitizen students and academics who have expressed pro-Palestinian views. Their justification? Similar to Palmer and Hoover in the early 20th century, the government claims they threaten national security. Now, as then, it was a specific kind of non-citizens speech with which the government took issue: what it deemed to be dangerous to American foreign policy interests. A look back at the story of the Palmer Raids can help us understand the administration’s efforts today.

Five dollars and a sewing machine

Goldman was born in 1869 in Kovno, part of the Russian Empire, and emigrated to Rochester, New York, at age 16 with five dollars and a sewing machine. She married and divorced a fellow sweatshop worker and naturalized immigrant, Jacob Kershner, who turned out to be impotent. After he threatened to kill himself, she tried to reconcile with him. But at age 20, she left him for good.

A labor activist, anarchist, and birth control proponent, she was first arrested in 1893 after giving a speech in Manhattan’s Union Square and charged with incitement to riot. She had penetrating blue eyes, spoke English with no accent, and lectured in German, Yiddish, and English. A lover once compared her voice to that of the angel Gabriel.

Fellow anarchist Alexander Berkman met her on his first day in New York City at a Lower East Side cafe in 1889. The two became close friends and sometime lovers, but he was imprisoned from 1892 to 1916 due to his unsuccessful attempt to assassinate steel baron Henry Clay Frick in retaliation for the deaths of striking workers. (Many years later, Goldman admitted to being a co-conspirator.) Unlike Goldman, Berkman never applied for U.S. citizenship.

Organizing against the war effort

On Sept. 6, 1901, a self-proclaimed anarchist assassinated President William McKinley, and police claimed that he had been inspired after attending a speech by Goldman a few months earlier. She spent nearly three weeks in jail but was released without charge.

In the wake of the assassination, states passed anti-anarchist laws and the federal government followed, chipping away at the First Amendment rights of anarchist and Socialist non-citizens. The Anarchist Exclusion Act, or the Immigration Act of 1903, prevented anarchists from entering the country and deprived them from the right to naturalization.

Shortly after its passage, an English anarchist, John Turner, was arrested after delivering a lecture in Manhattan, charged with promoting anarchism and violating alien labor laws, and detained for deportation on Ellis Island. Goldman went on a northeastern lecture tour to support Turner. By then she was internationally famous and drew tens of thousands to her lectures all over the country.

The short life of the No-Conscription League

Shortly after Congress declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, and it seemed certain that a Selective Service Act would be passed, Goldman, Berkman, and two fellow activists organized the No-Conscription League. In six short weeks, they circulated 10,000 leaflets, held mass meetings, and gave advice and information to young men who came to league offices.

President Wilson sought to frustrate the anti-war effort. In May and June 1917, he signed the Espionage Act, making it illegal to share information that could impede the military’s efforts or support the enemy — including efforts to obstruct the draft. The government arrested and convicted more than 1,000 activists opposed to the war.

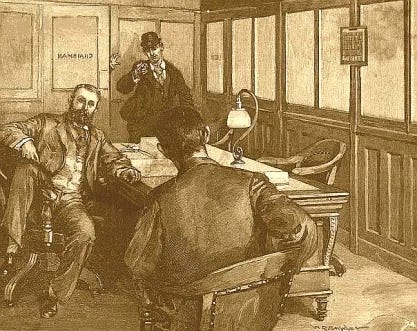

Four days after the Espionage Act was passed by the Senate, 8,000 people attended a mass meeting for the No-Conscription League at the Harlem River Casino. Authorities arrested Goldman and Berkman on charges that included conspiring against the draft under the Espionage Act. They were taken to “The Tombs,” the municipal jail, and each held on $25,000 bail.

We had hoped to welcome you back in life — but we welcome you back in death.

Their trial began on June 27 — Goldman’s 48th birthday. A military band at a recruiting station on the street outside the courthouse played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and everyone but Goldman and Berkman rose to their feet. “What could the officials do?” she wrote in her memoir. “They could not very well order us removed.”

In her two-hour courtroom summation, Goldman likened her patriotism to the U.S. to “that of the man who loves a woman with open eyes — enchanted by her beauty, yet he sees her faults.” Assailing the suppression of First Amendment rights, she said, “Shall free speech and free assemblage, shall criticism and opinion — which even the espionage bill did not include — be destroyed? Shall it be a shadow of the past, the great historic American past?”

On July 9, 1917, the jury found them guilty, and the judge gave each the maximum penalty and sentence: $10,000 and two years in federal prison. He also recommended deportation following their sentences.

Emma Goldman in prison

In the summer of 1917, after her lawyer Harry Weinberger’s appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected, Goldman began her prison sentence at the Missouri State Penitentiary. With deportation looming at the end of her sentence, Goldman had multiple chances to gain citizenship while in prison. One American supporter offered to adopt her, and one of her associates at “Mother Earth” offered to marry her. However, Weinberger advised her to decline.

Though Hoover and the Justice Department sought to deport Goldman, deportations were handled by the Immigration Bureau, which was within the Labor Department. This meant a senior official at the Labor Department had to sign her deportation orders. Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis Post was a one-time radical journalist who had known Goldman socially and refused to sign off on a previous deportation order against her. Now, feeling he had no choice after Goldman’s and Berkman’s convictions, Post signed their deportation orders.

While Goldman was in prison, Wilson’s crackdown on free speech continued. The Immigration Act of 1918, enacted in October, allowed the government to deport anarchists, communists, labor organizers, and other activist aliens.

Goldman was served with an arrest warrant and a deportation order on Sept. 12, 1919. Her former husband, Kershner, had been denaturalized as part of the government’s attempt to deport her. At her immigration hearing on Ellis Island, Weinberger unsuccessfully argued that a technical error in Kershner’s denaturalization meant that his, and Goldman’s, citizenships were valid.

Goldman might have been better off if she had remarried while in prison. Instead, she would now be deported back to Russia.

The First Red Scare and Hoover’s ‘square deal’ for Goldman

A few days after Goldman’s hearing, the Wilson administration launched what would become known as the Palmer raids. On Nov. 17, 1919, federal agents and local police arrested and beat Union of Russian Workers (URW) members in 12 cities throughout the Northeast and Midwest, with more than 1,000 arrested without warrants. URW members were anarcho-syndicalists, which meant they believed trade unions could be used to create revolutions.

Anguished about being deported, Goldman took Berkman on a lecture tour to Detroit. They drew 4,500 people and raised $5,000 for their defense. However, once back in New York, she was detained at Ellis Island and housed with two women who had been arrested in the most recent Palmer raid.

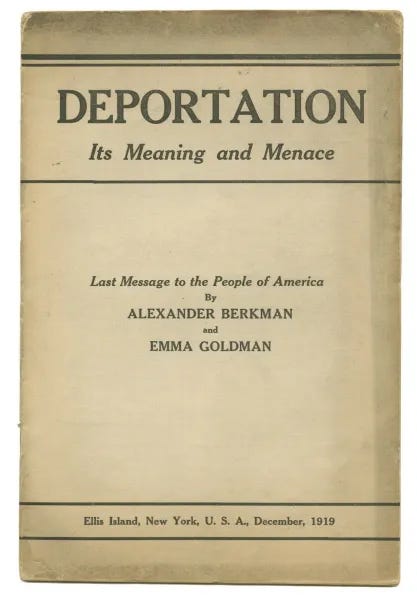

While in detention, she and Berkman wrote the pamphlet, “Deportation — Its Meaning and Menace,” in which they argued that her case set a precedent by which “the naturalized citizen may be disfranchised, on one pretext or another, and deported because of his or her social views and opinions.”

Around two in the morning on Dec. 21, 1919, in 20-degree weather, Goldman, Berkman, and hundreds of other deportees were awakened and taken into the Great Hall of Ellis Island. Guards then took them to a barge, pulled by a tugboat, to transport them across the harbor to Gravesend Bay in Brooklyn, where the Buford was anchored.

Through the porthole Goldman saw the New York City skyline. “It was my beloved city, the metropolis of the New World,” she would later write in her memoir. “It was America indeed, America repeating the terrible scenes of tsarist Russia! I glanced up — the Statue of Liberty!”

Hoover, around half Goldman’s age, was onboard.

“Haven’t I given you a square deal, Miss Goldman?” Hoover asked her.

“We shouldn’t expect from any person something beyond his capacity,” she replied.

The Buford deportees and Louis Post

Escorted by two uniformed officers to the ship, the 249 deportees were cursed and threatened by people who had come to watch in the middle of the night.

As Buford scholar Kenyon Zimmer has reported, nearly 90% of the deportees belonged to the URW. Some also belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World or newly formed Communist Party of America.

The oldest deportee was Goldman, age 50. The youngest, Timofey Pavlovich Bukhanov, had lived in the U.S. since he was seven. Only three of the passengers were women because the federal government was generally dismissive of radical women.

Eighty percent of the deported were repatriated to Russia, the rest to 29 other countries, mostly in Europe. The second round of violent Palmer raids in the U.S. would begin just a few weeks later.

About two months after the Buford left New York, with Hoover and Palmer hoping to deport hundreds more people, the secretary of labor went on leave. The assistant secretary who had once helped Goldman, Louis Post, was now in charge. In one month, he invalidated nearly 3,000 Palmer Raid arrests and released many of those held on Ellis Island.

Out of nearly 2,500 cases of communists, he allowed less than 20% to be deported. If arbitrary search and seizure uncovered evidence of illegal organizational affiliation, he threw out the case. If a potential deportee had been denied access to counsel, he threw that one out, too. A House Rules Committee investigated him but he was not removed, instead retiring in 1923.

The Bolshevik myth

Goldman fled Russia in 1921, having become disillusioned with the Bolsheviks, who seized power in the October Revolution of 1917. Berkman lived illegally in Germany, France, and elsewhere across Europe and wrote “The Bolshevik Myth,” criticizing the Soviet regime. With his health failing, he committed suicide in Nice in 1936.

Goldman lived in Riga, Latvia, and later Berlin and London. Peggy Guggenheim found her a cottage in Saint-Tropez, and Goldman completed her memoir, “Living My Life".

She returned to the U.S. for the first time since her deportation in February 1934 to deliver a lecture on her memoir and modern drama. After her visa expired she went to Toronto, where she filed a request to enter the U.S., hoping to reinvigorate a lecturing tour. The request was denied. With World War II looming, she worked in Toronto to support Spanish anarchists. In February 1940 she suffered a stroke and was unable to speak. She was pulled out on a stretcher and, in a gesture of modesty, pulled her skirt hem below her knee. She died a few months later, but she wouldn’t remain in Canada.

Immigration authorities allowed her body to be returned to the U.S., where she was buried in Chicago’s Waldheim Cemetery. At her funeral, her longtime friend and lawyer Harry Weinberger said: “Emma Goldman, we welcome you back to America, where you wanted to end your days with friends and comrades. We had hoped to welcome you back in life — but we welcome you back in death.”

Amy Sohn is the author of 13 books, including the award-winning The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, & Civil Liberties, which includes several chapters on Emma Goldman’s role in the modern birth-control movement. For those interested in learning more about immigrant radicals and the Red Scares, Sohn recommends Adam Hochschild’s American Midnight.