This article builds upon my previous gender and tolerance article. If you haven’t already read it, I highly encourage you to. You may also find it helpful to read that article’s addendum, as well as the raw data, codebook, and code used to generate the plots in this article. Also, keep in mind there’s a shorter version of this post available that was written for a general audience, which you can find in the Data Dive section.

I recently wrote about the significant gender tolerance gap. That naturally raises another question: are there controllable factors that actually help make people better or worse on this front? One obvious candidate is political involvement. Maybe political participation broadens people’s exposure to clashing viewpoints and forces them to wrestle with ideas they’d otherwise ignore. Maybe it teaches civic virtues like freedom of expression. Or maybe it simply funnels them into ideological echo chambers where bad habits grow and tempers get sharp.

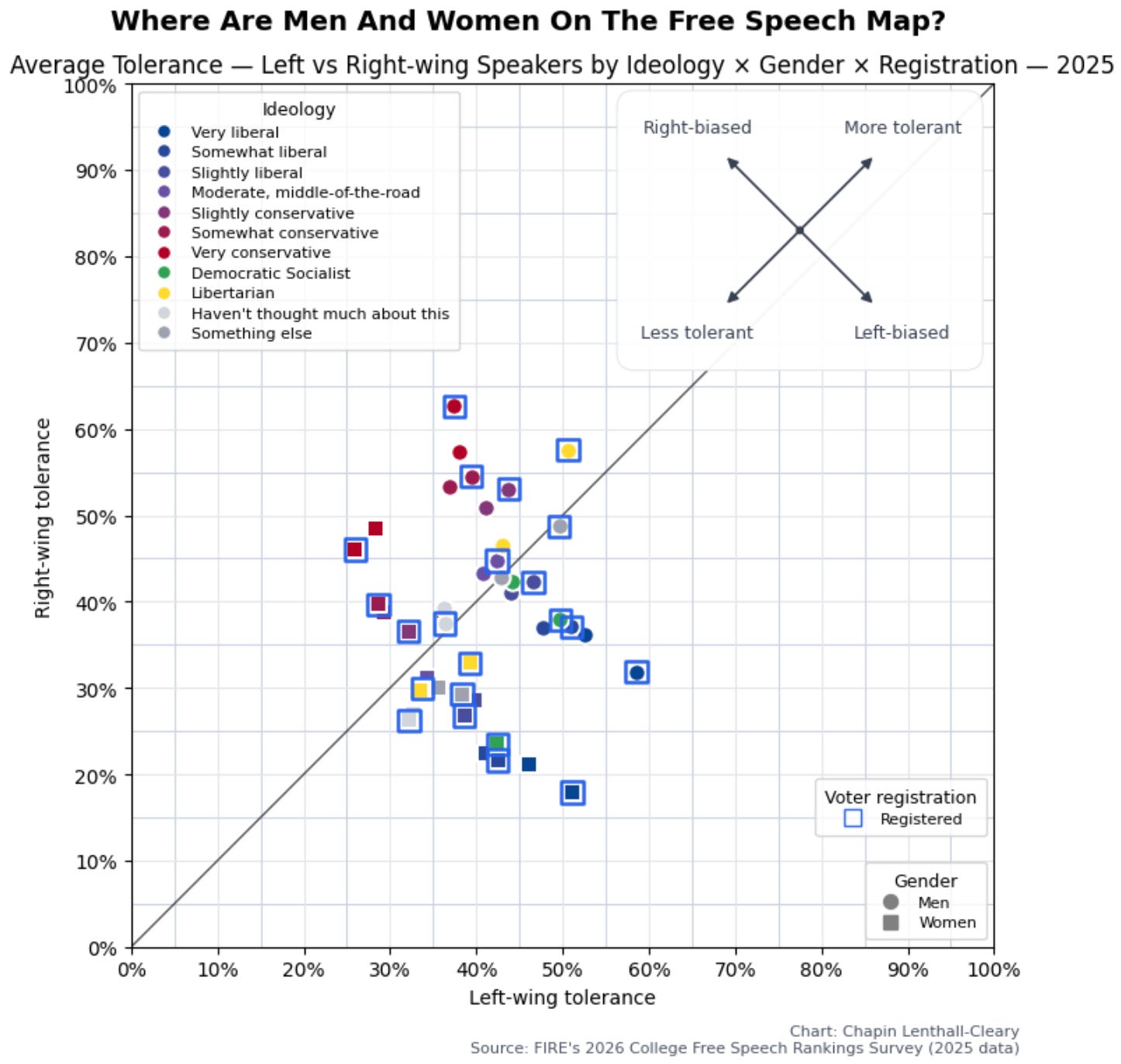

Turns out both stories might be true — just not for the same genders:

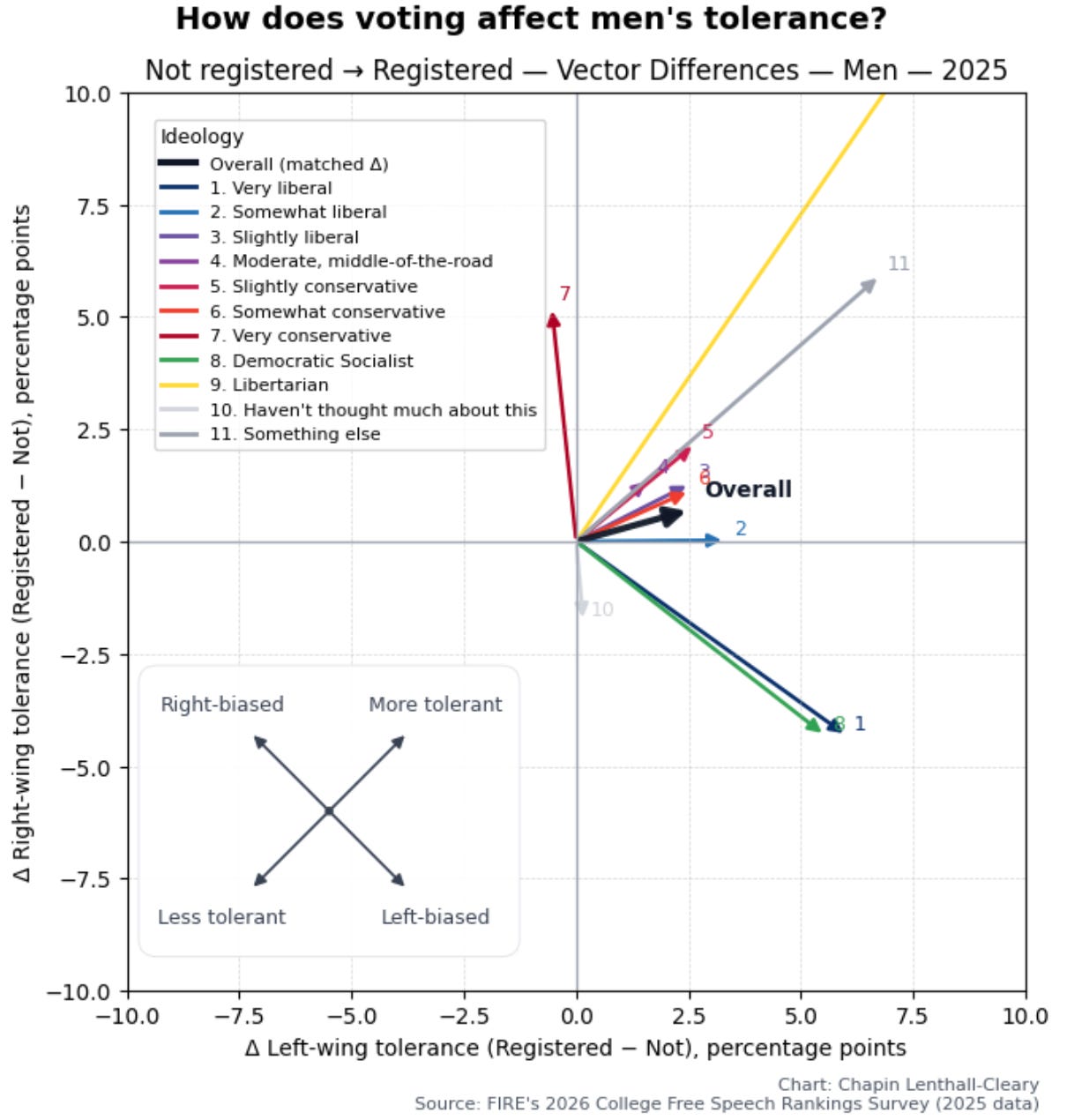

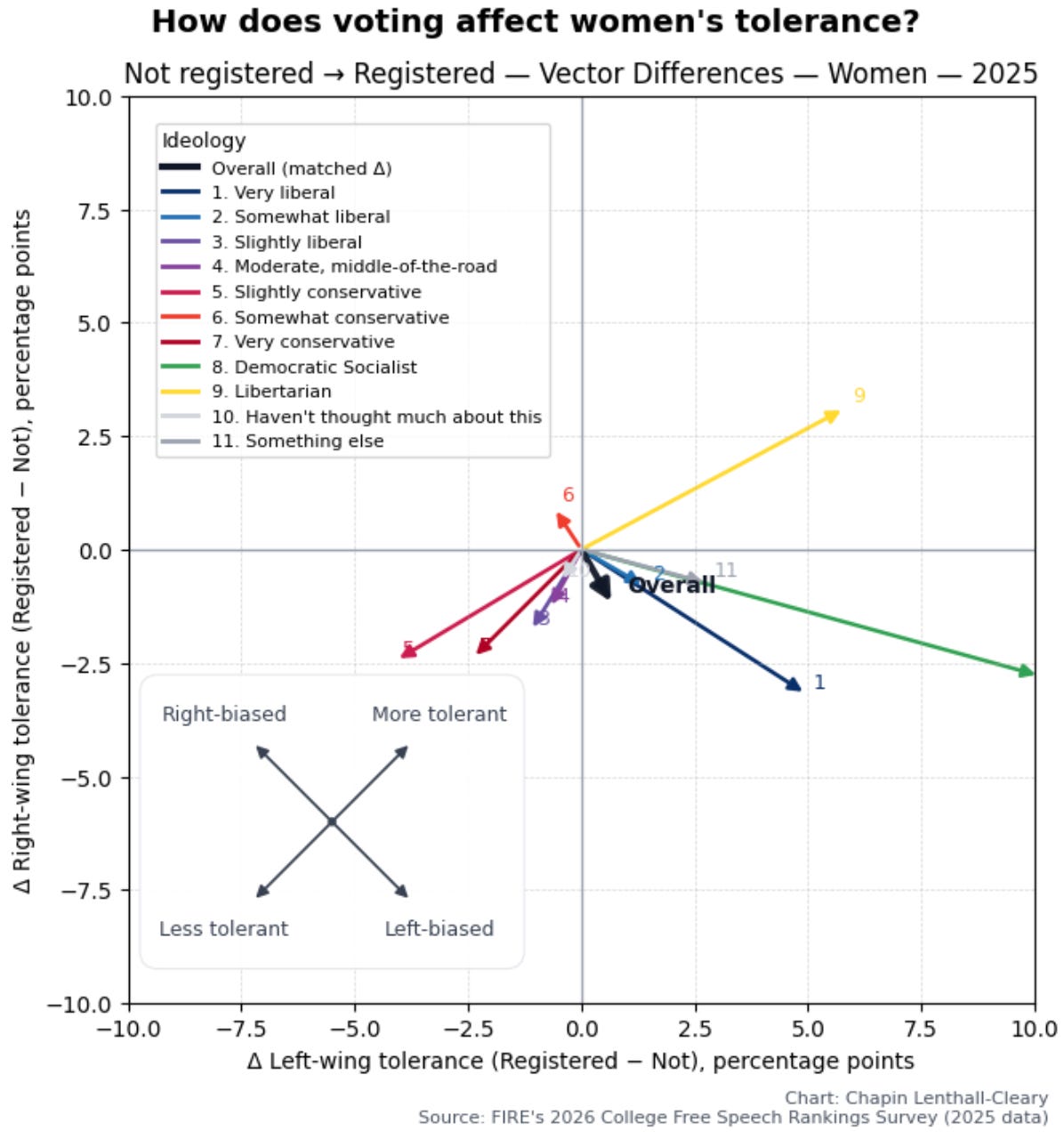

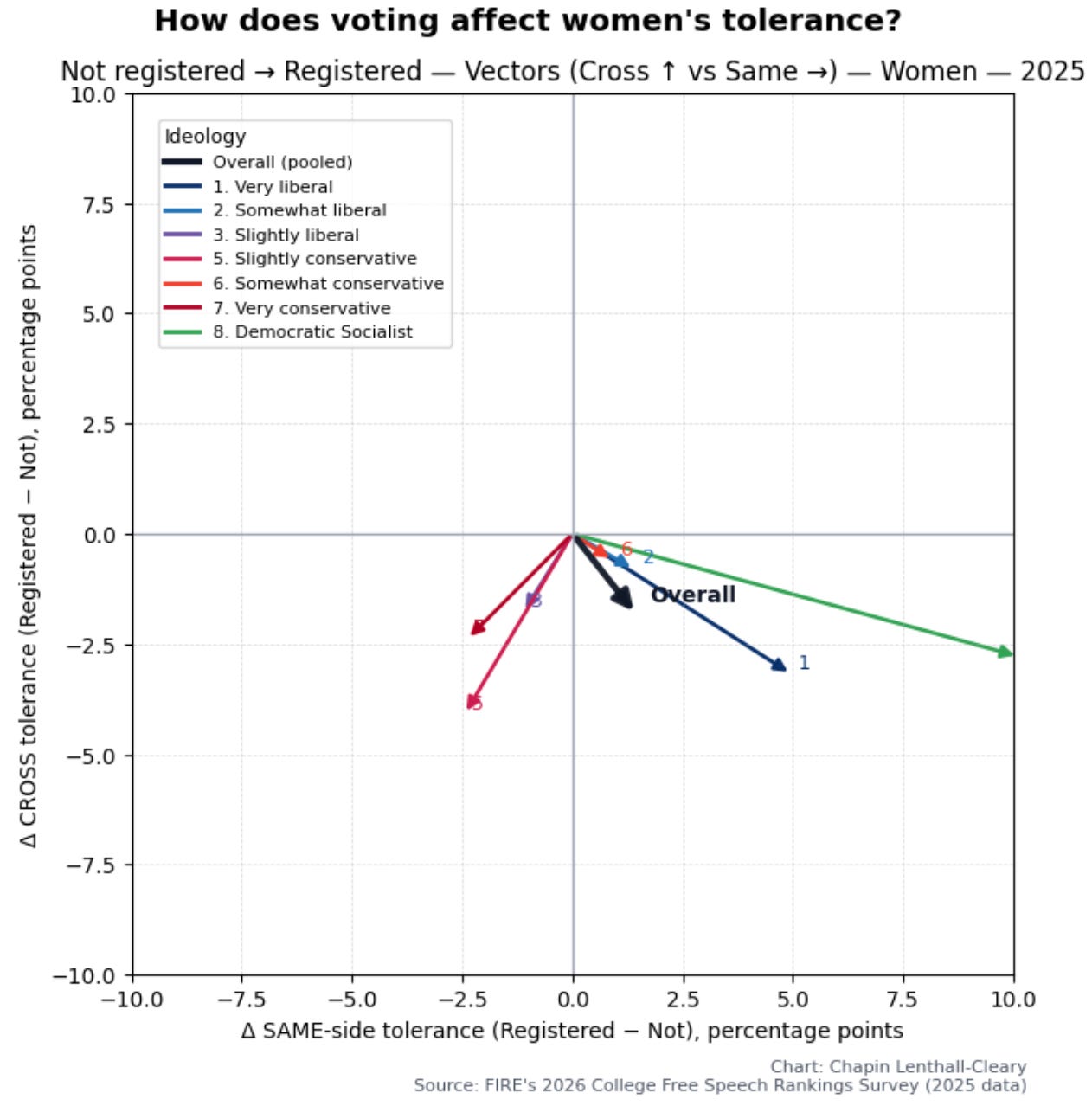

Okay, that’s a jumble. To make this clearer, let’s look at how voter registration changes the tolerance within each ideology. The following are vector difference plots (arrows showing change) in the same space as the free speech maps, illustrating the shift from people who aren’t registered to vote to those who are. Arrows pointing up and to the right would mean that those voters are more tolerant of both sides than non-voters:

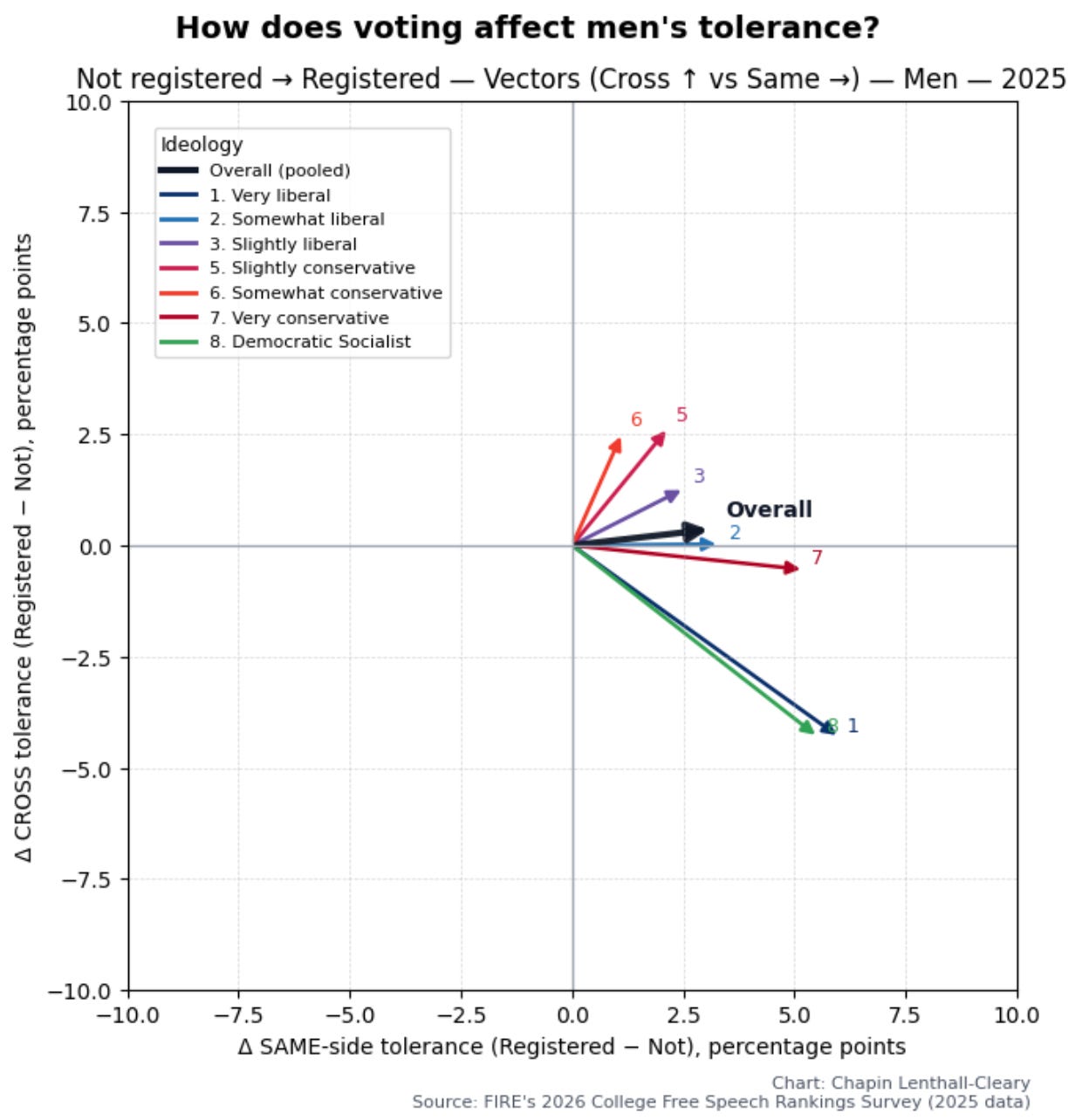

Wow. So being registered to vote generally makes male students more tolerant, and often makes them more tolerant of both sides, whereas it almost always makes women less tolerant of the right, and often less tolerant of the left too. We can put a finer point on this by plotting cross-tolerance on the same axis for everyone. Here, tolerance for the opposite side is on the y-axis (going upward) and tolerance for the same side is on the x-axis (going to the right):

Men who are registered to vote are more tolerant of the opposite side than men who aren’t. But women who are registered to vote are not only less tolerant of the opposite side than women who aren’t, but also less tolerant overall. (The overall values use an average weighted by n of the smaller sample in each pair. I think this is the best way to do this, but I’m not confident of that. Simply subtracting one average from another produces a similar pattern, though a slightly smaller gender difference.)

There’s also an ideology effect. Ideologically extreme men become more tolerant on average when they register to vote, but also more polarized. But moderate men are golden, becoming more tolerant of both the other side and their own.

You might wonder whether this effect is driven by age. After all, older students are slightly more tolerant. But if it were, we’d expect to see men and women affected similarly, which they aren’t. Also, if we bin by age, the gender gap doesn’t go away (see our code for details.)

Another interesting note here: men who say they haven’t thought much about their ideology, who patterned with women on the free speech map, also pattern with women here, becoming less tolerant (particularly of the right) when they’re registered to vote. I don’t immediately know what to make of that, but it hints at a possible deep similarity between men who haven’t thought much about ideology and women.

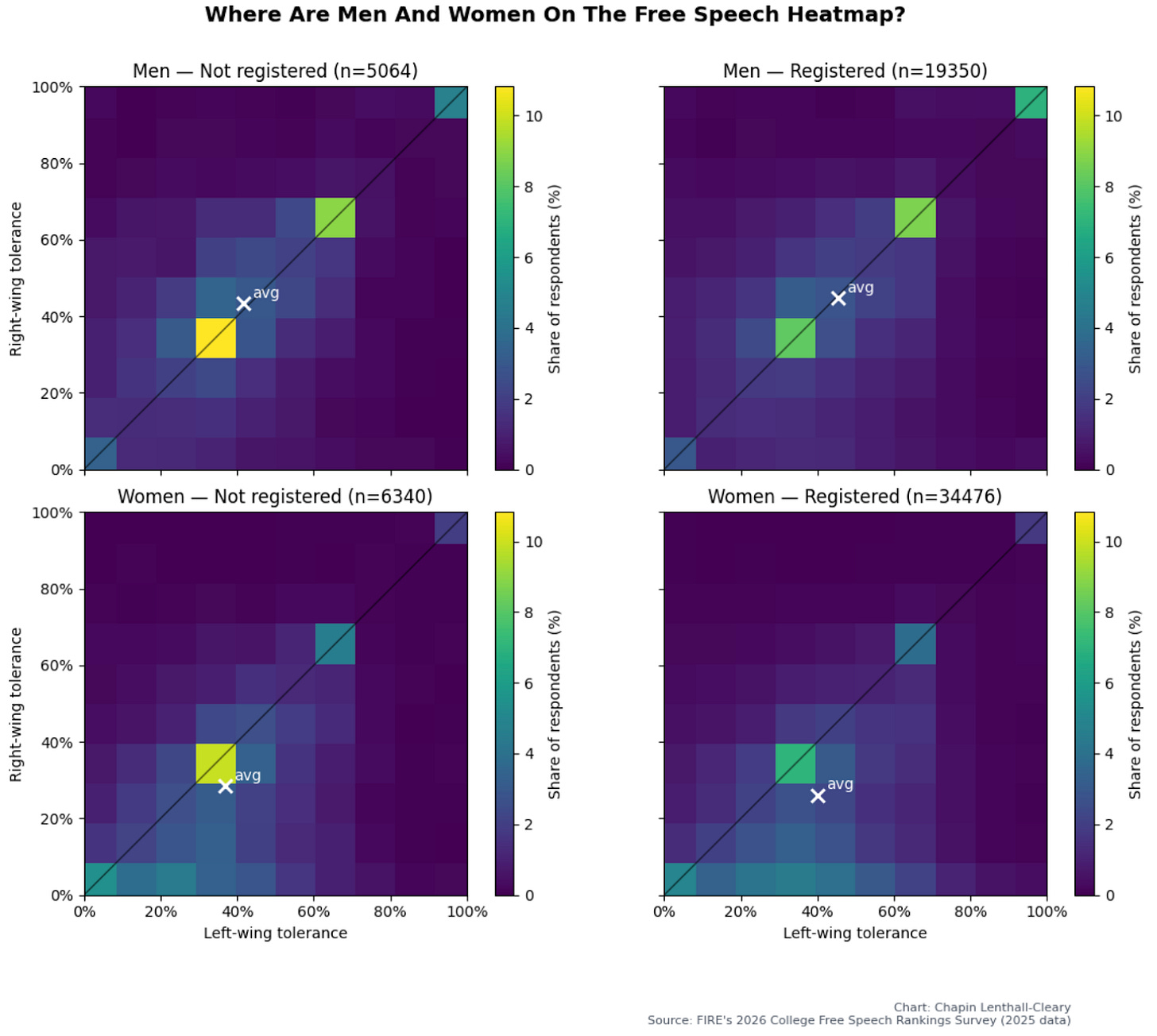

Let’s look at a heat map:

A few things stick out here. When unregistered, both men and women are more likely to be at the bright square ⅓ of the way up each axis. This corresponds to answering “probably not” for the question of allowing every speaker, a “shut-up-and-let-me-sleep” default (relatively censorious) answer. But when registered, they’re pulled in wildly different directions. Men become more likely to be perfect, whereas women are more likely to occupy the middle of the bottom row, somewhat censorious of the left but absolutely intolerant of the right. The effect isn’t massive, but being registered to vote pulls men towards the enlightenment ideal and pulls women towards the woke stereotype.

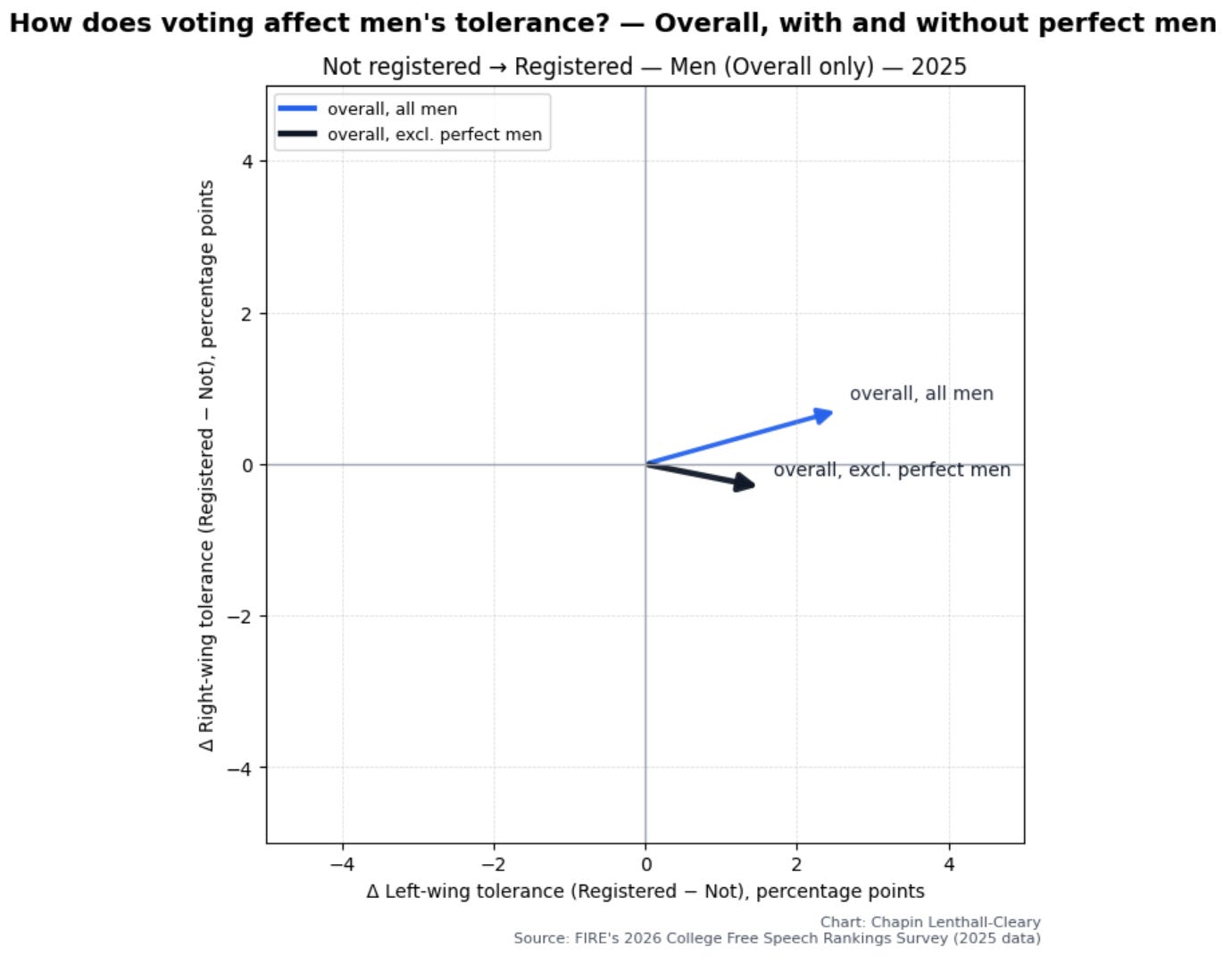

To crudely illustrate how much of the effect for men is driven by perfect men, we can recalculate men’s overall vector difference excluding perfect men and compare that to the actual overall vector difference (yes, I know the issues with this method):

Obviously, these results don’t prove the direction of causation, and I don’t yet have any strong evidence either way. It’s possible that being involved in politics brings out the best in men and the worst in women, that better men and worse women are more likely to participate politically, or both. All those possibilities have profound impacts and suggest avenues to improve tolerance, but in different ways, so it’s important to try to figure out which is true.

If political participation drives tolerance, or intolerance, that suggests that there are potential avenues to improve tolerance by changing how people engage politically. Could we teach women to engage in politics in the way that men do? Would that also make women more tolerant? What exactly is the male way of engaging in politics, and why does it work better on average?

There’s a lot of variation within men too. Could we teach more men to engage in the way that works really well for some others? If not, could we at least push people away from engaging in politics in the way that makes women worse? And a small minority of women have beaten the trend. Could other women do whatever they’re doing right? Would courses in free speech or training in philosophy or rational debate help? What about stigmatizing being unwilling to engage in rational debate (and change your mind if the evidence demands)?

If the effect is driven by more tolerant men and less tolerant women being more likely to engage politically, that would leave us with some tough questions. Are there ways to get the minority of tolerant men who don’t engage politically to do so? Are there ways to get the people, mainly women, who are most intolerant to engage in politics in a more tolerant manner? And if not, what then?

It’s worth emphasizing that, while I have some ideas that I consider promising, I’m not confident about what any solutions are. But there are deeply important, and perhaps uncomfortable, questions about how we conduct discourse and engage with politics here. Most people are more censorious than we’d like, but women engaging in politics are disproportionately driving this problem.

The problem may look intimidating, but there’s nothing here that says it can’t be fixed. If we want to correct our failures through open debate, we’ve got to understand what’s driving this — and then get to work on fixing it.

Some guesses on what drives men who don’t think about politics patterning with women:

1. Men who don’t think about their ideology are more likely to profess whatever beliefs will make them popular with women, or to get their political information from their wives and girlfriends.

2. Men who think about their ideology tend to get their information from less mainstream sources than women and men who don’t think about their ideology.

3. Men who think about their ideology tend to debate a lot, women and men who don’t think about their ideology don’t often debate.