When speech no longer seems sufficient, part II

When I went back to class — and still couldn’t make the case for persuasion

Last week, I wrote that students are beginning to treat speech as insufficient, as though persuasion is a kind of performance and disruption or violence is the only thing that works. I shared my own attempt to explain this to my students. But that lesson didn’t go as I had hoped.

I left that class unsettled, and more than a little upset, realizing that so many of my students seem unmoved by the premise that words are a better alternative to force. I promised myself I would go back and try again. I thought that if I returned with more evidence, more history, and the strongest strategic case for why violence fails and persuasion matters, the point would land.

So I went back. I went prepared. I took more than moral exhortation. I took the best empirical record we have about political change. And I left feeling unsure that my students had even heard me.

Some of my students now speak as though persuasion is a dead letter. Many talk about political violence in ways that would have been unthinkable even a few years ago. Not as an absolute moral boundary, but as an understandable necessity when words are insufficient. That’s not a caricature. It’s something I have heard, more than once, in ordinary classroom conversation. One student put it to me plainly after class: “Persuasion assumes the other side is reachable. What if they’re not?”

“You’re asking us to play by rules that only one side follows,” another said. I haven’t been able to shake the comment, mainly because these objections are not out of bounds. They are, in fact, the objections of students who have been paying attention, who have watched institutions fail, watched speech get met with silence, and watched power operate without accountability. So I understand the frustration. Indeed, I share some of it. But understanding where the impulse comes from does not mean the impulse is right. I tried to meet the mood of escalation with evidence.

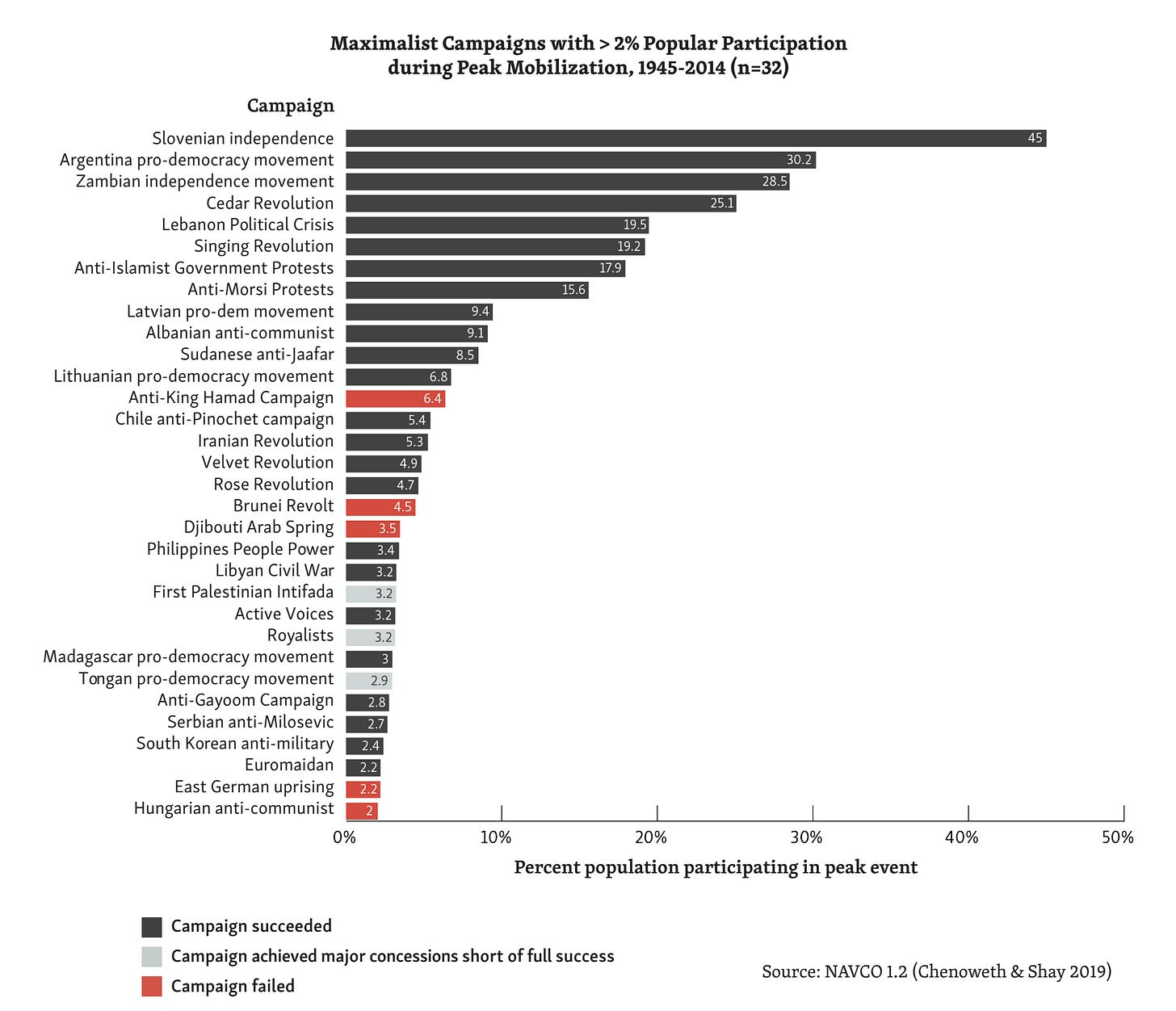

I brought Erica Chenoweth’s research into the room. Chenoweth, working with Maria J. Stephan, studied 323 major resistance campaigns — violent and nonviolent — across the last century. Their findings, published in Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, are striking: nonviolent movements succeeded roughly twice as often as violent ones. By their measure, about half of nonviolent campaigns achieved their goals, compared to roughly a quarter of violent insurgencies.

The reason is simple. Nonviolence works because it invites participation. Violence narrows movements to the most radical and risk-tolerant members of a group, but nonviolence broadens movements to include ordinary people — workers, parents, students, clergy, professionals — whose participation gives a campaign real moral force and civic legitimacy. That scale matters because, as the data shows, it means that nonviolence is actually more powerful.

This is also the logic behind Chenoweth’s much-discussed 3.5% rule. In the historical record they examined, no government withstood a sustained nonviolent campaign that mobilized active participation from roughly 3.5% of the population. The point is not that 3.5% is some magic number. Chenoweth has been clear that it’s a descriptive pattern, not a mechanical formula. Nevertheless, the general pattern suggests that disciplined mass participation, rather than escalation, is what makes movements succeed.

Participation at that scale produces something even more important: shifts in loyalty. When resistance remains nonviolent, pillars of institutional support — bureaucracies, elites, even security forces — are more likely to defect or refuse repression. That’s how durable political change actually happens. In other words, nonviolence is not passivity. It’s organized power under restraint. I already know the objection. I heard it in class. Chenoweth studied campaigns against dictatorships and foreign occupations, not campus speaking events. What does overthrowing Milosevic have to do with whether a student should sit politely while a speaker they find complicit holds a microphone?

But that objection misunderstands the research. The logic of participation, legitimacy, and loyalty shifts does not operate only at the level of regime change. It operates wherever people are trying to move institutions. A campus is an institution. A faculty is a constituency. An administration is a structure of authority that can be persuaded, pressured, or alienated.

The erosion I am describing does not begin with violence. It begins with the abandonment of persuasion — first as a tactic, then as a value. Disruption, even when nonviolent, operates on the same strategic logic as the violent campaigns Chenoweth studied, and similarly narrows participation while forfeiting legitimacy. The students who disrupt a talk may feel powerful in the moment, but they are narrowing their movement to those who are willing to shout, or who condone such behavior, while surrendering the very breadth of participation that makes institutional change possible. The strategic logic is the same at every scale. Movements that drive people out lose. Movements that invite people in win.

That’s what I tried to tell my students. And yet the most unsettling part of this moment is that the data does not settle the question. The evidence does not end the argument. For some students, it barely enters it. The numbers felt beside the point. The historical cases felt distant. The strategic logic could not compete with a deeper mood: that speech is merely performative, and that power yields only to force or coercion.

We should be honest about what is happening here. The civic taboo against political violence is no longer as firm as it once was. PRRI’s national surveys have found a disturbing rise in the share of Americans, especially younger Americans, who now say political violence can be justified. My students are not outliers. When I stand in front of a classroom of 18- and 20-year-olds and try to make the case for persuasion, I am speaking to a generation in which the premise itself is increasingly contested not at the fringe, but near the center. What once would have been unthinkable is now, in some circles, understandable.

One can see the infrastructure of this shift everywhere. At Columbia University, the pattern is visible in compressed form. Just days ago, an anti-ICE protest outside campus gates led to the arrest of students and faculty who blocked traffic. They were being disruptive, but nonviolent. Yet it was less than two years ago that protesters occupied Hamilton Hall, barricading entrances, breaking windows, and trapping staff inside until the New York Police Department was called to clear the building. The speed with which disruption becomes something worse is itself part of the story. This dynamic is also present at my institution. When Ezra Klein visited to speak, a group of student protestors disrupted the event and later defended the disruption as not only justified, but morally required. In their telling, Klein’s talk “necessitated disruption.” Allowing him to speak was itself framed as complicity.

This is the logic of the heckler’s veto in its purest form — the idea that speech one finds objectionable does not deserve to be answered but prevented, that the appropriate response to disagreement is not argument but disruption, and that the highest civic act is not persuasion but silencing. It is a rejection not only of a speaker, but of the entire premise of democratic contestation.

Afterward, I asked my students what they thought. Several did not see it as a serious problem. A few agreed with the underlying premise that certain speakers fall outside the bounds of legitimate discourse, and that preventing them from speaking can be framed as justice rather than censorship. Once again, speech had become optional. Once again, persuasion did not feel like the point. When speech no longer seems sufficient, coercion begins to feel necessary. And once disruption is normalized as “expression,” it becomes much harder to explain why escalation should stop there.

And yet restraint is precisely what our campuses are struggling to teach. One reason is that the ground has been prepared — over years, often with the best of intentions — by a culture that treats emotional discomfort as a form of harm. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt diagnosed this in The Coddling of the American Mind, calling it “safetyism,” or the belief that exposure to opposing views is not an invitation to argument but a kind of threat. Safetyism is not the same thing as the rejection of persuasion, but it is the soil in which that rejection grows. If students have already been trained to experience disagreement as injury, then the leap from “speech is harmful” to “speech must be stopped” becomes not radical but intuitive. And from there, the leap to “only force changes anything” is shorter than any of us would like to admit.

In such an environment, students are not trained for democratic conflict. They are trained for moral emergency. Disagreement becomes trauma. Debate becomes violence. And once you begin to treat speech itself as an injury, it becomes easier to justify coercion as “self-defense.”

Let me be honest about something else. My students are not entirely wrong about the world they have inherited. They are right that institutions have failed. They are right that powerful people have spoken beautifully and done nothing. They are right that some speakers are brought to campuses in bad faith, as props in a culture war rather than as participants in genuine inquiry. The diagnosis is often correct.

It’s the prescription that is dangerous. The conclusion they draw — that because persuasion sometimes fails, it should be abandoned — does not follow from the evidence. The right conclusion is that persuasion, though difficult and often unrewarding, is still better than every alternative. Not because nonviolence is morally pure, but because it is strategically superior. Not because speech always works, but because what replaces speech always works worse.

The great temptation of our moment is to believe that if speech does not immediately produce the world we want, then speech must be discarded. But history suggests the opposite. Speech is not the obstacle to democratic change. Speech is the beginning of democratic change. When speech is abandoned, the only remaining tools are coercion and force, and those tools do not elevate politics. They brutalize it.

The first time I confronted my class, I made the case from the heart. The second time, from the evidence. Neither landed. But that’s not a teaching problem. That’s a cultural problem. The issue is not the substance of the argument so much as the fact that the ground on which the argument stands has shifted beneath us. I have no third approach lined up. I am not sure one exists. My students listened, but I am no longer sure they heard. Still, I will walk back into that room next week, because the day I treat my own classroom as a lost cause is the day I concede that they’re right — that persuasion really has failed.

It sounds to me that it is not their opponents writ large who are the ones that are unreachable by persuasion. If this attitude is widespread among the educated youth, then that worries me deeply. To the best of my knowledge, revolutions generally don't begin amongst the working class. They tend to begin with disgruntled elites, propelled by the justifications of intellectuals. Despite all of our current problems, those problems pale in comparison to the horrors that widespread political violence brings. Just ask Lebanon.

At what point and how does speech intersect with knowledge and truth? Our world and the college campus - often the factory of fantasies - is filled with monstrous hoaxes, dogma and inventions. Do these students ever entertain the notion that they might be wrong? They need a lesson in knowledge as much or more than a lecture on free speech. A short history tour of the 1930’s intellectual glorification of communism would be a good start.