Politics of dissent during World War I

When socialists, anarchists, and other political dissidents opposed the war effort, Woodrow Wilson had their movements crushed.

It is commonplace to say that the First Amendment protects the dissenter, the one who challenges the status quo, pushes the envelope, or advocates for fundamental change. But this was not always the case in American history. The time of World War I may provide the most salient example.

President Woodrow Wilson had won re-election in 1916 on the promise to keep the United States out of World War I. Yet early in his second term, with the country on the precipice of war, Wilson had to sell the war effort to a doubting nation. He created something known as the Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, to drum up support for U.S. entry into the war. Wilson, Creel, and the Wilson administration waged war with messianic zeal against anyone who opposed the war effort.

![Drawing shows Uncle Sam rounding-up men labeled "Spy," "Traitor," "IWW," "Germ[an] money," and "Sinn Fein" with the United States Capitol in the background displaying a flag that states "Sedition law passed" referring to the Sedition Act of 1918. Drawing shows Uncle Sam rounding-up men labeled "Spy," "Traitor," "IWW," "Germ[an] money," and "Sinn Fein" with the United States Capitol in the background displaying a flag that states "Sedition law passed" referring to the Sedition Act of 1918.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9Vge!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fffc25196-1ad8-4c68-bf8a-537c50a0e0c2_417x534.webp)

According to the Wilson administration, failure to support the war and the draft was tantamount to disloyalty. U.S. Attorney Thomas Gregory delivered a speech at Lincoln Memorial University in November 1917, warning in no uncertain terms about the consequences of opposing the war effort: “Our message will be delivered to them through the criminal courts all over the land. And may God have mercy on them, for they need expect none from an outraged people and an avenging Government.”

Gregory and others in the administration were true to their word in pursuing and prosecuting, with more than 2,000 persons prosecuted for violating the Espionage Act. The law criminalized efforts to obstruct or interfere with the U.S. war effort. In effect, it was used to silence political dissenters. Thousands of individuals were prosecuted under the law.

The Supreme Court clampdown on dissident speech

There is a reason why legal historian Paul Murphy titled his famous book on free speech during this time as World War I and the Origin of Civil Liberties. Before the time of World War I, the Supreme Court was not focused on individual rights. The Court cared more about property rights. But this was a new day. Political dissidents of different stripes were at risk: socialists, communists, anarchists — you name it.

In the spring of 1919, the Supreme Court decided several cases involving political dissenters who were prosecuted and convicted for allegedly violating the Espionage Act. Foremost of these were the trilogy of Schenck v. United States, Frohwerk v. United States, and Debs v. United States. Collectively, these three decisions often are considered the beginning of the Court grappling with whether the First Amendment protected political dissident speech during wartime. The Court unanimously affirmed the convictions of the defendants in all three cases.

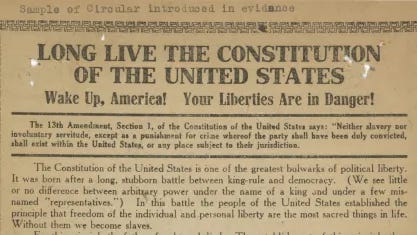

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote all three opinions. The first case, Schenck, involved the prosecution of Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer for distributing leaflets in New York City that were critical of the draft and the war. Schenck was the secretary general of the American Socialist Party and Baer was on the group’s executive board. The double-sided leaflet — quite tame by modern standards — railed against the draft as a monstrosity against humanity and quoted the Thirteenth Amendment. On the other side, it urged people to “Assert Your Rights.” It read: “You must do your share to maintain, support and uphold the rights of the people of this country.”

In his opinion, Holmes determined Schenck’s political speech crossed the line and caused harm to the country. He famously introduced the phrase “clear and present danger,” writing that words ordinarily protected “may become subject to prohibition when of such a nature and used in such circumstances as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils which Congress has a right to prevent.” He added that what might be uttered in times of peace may not be tolerated or protected during times of war. Clearly Holmes was convinced that the leaflets violated the Espionage Act, as they urged readers to avoid and actively oppose the draft.

Frankly, the court’s opinions in the Schenck-Frohwerk-Debs trilogy failed to protect free speech. Anti-war speech and political dissent lost badly in all three cases.

Only one week later — on March 10, 1919 — the Court released Holmes’ unanimous opinion for the Court in Frohwerk. Jacob Frohwerk was the copy editor for a German-language newspaper, the Missouri Staats-Zeitung. Frohwerk asserted that Germany did nothing wrong to the United States, certainly nothing that justified the country entering the war. Citing his opinion in Schenck, Holmes noted that “a person may be convicted of a conspiracy to obstruct recruiting by words of persuasion,” and he concluded there was little difference between the offending language in the two cases.

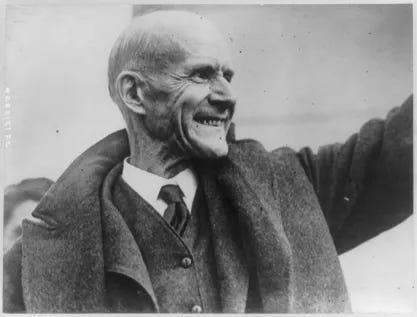

The same day, the Court also reached its decision in Debs. Unlike the defendants in Schenck and Frohwerk, Eugene Debs was a household name. He was the nation’s leading pro-union advocate and a multi-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America. On June 16, 1918, he delivered an anti-war speech in Canton, Ohio. Debs knew that he was being monitored closely by the Wilson administration but bravely told the crowd, “You need to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.”

In his speech, Debs praised the socialist cause, advocated for peace, and inveighed against militarism and war, but he was also prescient about having limited free speech rights and the need for prudence:

I realize that, in speaking to you this afternoon, there are certain limitations placed upon the right of free speech. I must be exceedingly careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and prudent as to how I say it. I may not be able to say all I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.

Soon after his speech, federal authorities deemed the speech too disruptive to the draft and the overall war effort and arrested Debs for violating the Espionage Act of 1917. As amended by the Sedition Act of 1918, this law was a direct assault on free speech, making it a crime to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States.” Holmes reasoned that Debs’ anti-war speech in Canton was designed to obstruct draft recruiting and once again affirmed a conviction against a political dissident speaker.

Frankly, the court’s opinions in the Schenck-Frohwerk-Debs trilogy failed to protect free speech. Anti-war speech and political dissent lost badly in all three cases.

The coming of the ‘Great Dissent’

Something significant happened over the summer months of 1919. Holmes corresponded with Judge Learned Hand, Harvard law professor Zechariah Chafee, and a young political scientist from Harvard named Harold Laski. None of them agreed with Holmes’ free-speech opinions and told him so in different ways. Holmes immersed himself in study and lucubration and emerged with a more nuanced understanding of freedom of speech.

Holmes’ dissent in Abrams is considered the birth of modern First Amendment jurisprudence.

The arc of Holmes’ redemption culminated in his dissenting opinion in Abrams v. United States (1919), a case involving the prosecution of five Russian immigrants — Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Samuel Lipman, Jacob Schwartz, and Mollie Steimer — for criticizing U.S. policy towards Russia. They were convicted and sentenced to 20-year terms and banishment from the country. Their convictions were upheld on appeal, including a 7-2 ruling from the Supreme Court.

The Deported

In 1919 and 1920, acting under orders from President Woodrow Wilson, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer arrested as many as 10,000 so-called radicals, many of them labor activists, without regard for their constitutional rights. He also succeeded in deporting more than 550 noncitizens. He did this under the authority granted by the...

But Holmes authored what law professor Thomas Healy calls “the Great Dissent” in his book by the same name. Holmes strengthened the clear and present danger test, by requiring that there be some level of immediacy between the speech and resulting harm before conviction.

“It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned,” he wrote.

In arguably the most stirring passage in the history of free-speech jurisprudence, Holmes wrote:

But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.

This passage introduces what has come to be known as the marketplace of ideas rationale — still a pervasive metaphor in modern First Amendment law. The idea is that it is better for the government to allow all ideas into the marketplace rather than to censor ones it does not like.

Holmes’ dissent in Abrams is considered the birth of modern First Amendment jurisprudence. It endures even today. His dissent led to the Court’s adoption — many decades later — of the high standard from Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) that even advocacy of illegal conduct is protected expression unless it incites imminent lawless action. As Thomas Healy concludes in The Great Dissent, Holmes’ “metaphor of the marketplace of ideas and his concept of ‘clear and present danger’ have worked their way into our collective consciousness, becoming part of our language, our view of the world, and our identity as a nation.”

Related pages

Supreme Court Decisions: DEBS v. UNITED STATES, SCHENCK v. UNITED STATES, FROHWERK v. UNITED STATES, BRANDENBURG v. OHIO

The emails I'm getting have terrible typos and poor wording all through them.

I'm guessing this is a Substack artifact?